It’s Time to Document Teaching Styles More Carefully

September 2, 2014

Matthew Hora

Discussions of college classroom teaching styles often categorize them as either “lecture” or “interactive.” But those terms do not reflect the realities of classroom practice.

College-level teaching is more complex and nuanced than ever, and simple descriptors such as “lecturing” or “interactive” don’t tell us much.

Reducing how an instructor teaches Biology 101 to a variable such as “lecturing” masks other important dimensions of her teaching. What kind of questions does she ask students? How often? How are students socially and cognitively engaged in the classroom? How is technology used?

Those who evaluate classroom teaching can record their observations using a number of tools, but most are limited: They rely on open-ended response items that preclude reliability tests or comparison across individuals; they focus only on the use of teaching methods; they ignore temporary fluctuations in teaching practices throughout a class period; or they equate instructional quality with one teaching method.

WCER researcher Matthew Hora says developing a more nuanced and detailed knowledge of college teaching styles will help determine what is most likely to benefit student achievement. In a recent study Hora and colleague Joseph Ferrare used a tool called the Teaching Dimensions Observation Protocol (TDOP). http://tdop.wceruw.org/

Based on an instrument WCER researcher Eric Osthoff developed for studying middle school science teaching, the TDOP captures subtle and dynamic realities of classroom practice that an exclusive focus on teaching methods would miss. Hora and Ferrare used TDOP to evaluate the teaching of 58 math and science faculty in classrooms at three public research universities.

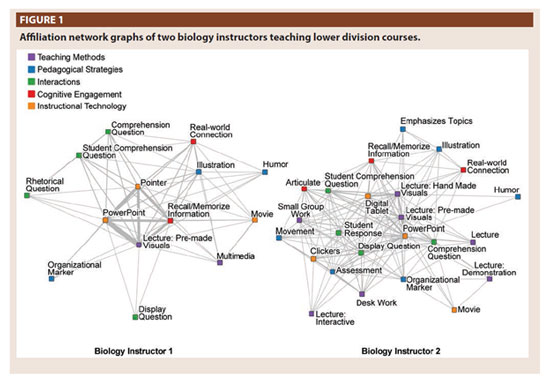

TDOP captures five dimensions of teaching practice: teaching methods, pedagogical strategies, student-teacher interactions, cognitive engagement, and use of instructional technology. Besides recording observable teaching methods such as lecturing or small group work, TDOP records instructors’ use of strategies such as humor, illustrations or anecdotes, and verbal transitions between topics. TDOP documents student-instructor dialogue and student-focused instruction. And TDOP captures how faculty use smart boards, digital slides, clicker response systems, and demonstration equipment.

Using TDOP, observers record classroom events in 5-minute intervals. Multidimensional graphs can be constructed that capture the teaching behaviors of each instructor across the five dimensions, and then compared across individuals or groups. Figure 1 (below) compares the teaching activities of two biology instructors.

One lecturer supplemented PowerPoint slides with a relatively small range of additional behaviors including illustrations and anecdotes, humor, conceptual questions, and multimedia, which were then associated with one type of potential student cognitive engagement (i.e., recall and memorize information). In contrast, the other instructor used five forms of lecturing, instructional technologies associated with a variety of cognitive engagements, and student interactions.

The two network graphs shown in Figure 1 illustrate that, although both instructors lecture for most of the class, each used a different repertoire of teaching behaviors to convey the course material to students.

Hora says descriptive research about postsecondary science teaching is important in the same way that careful observations of phenomena are central to the scientific method. Detailed descriptions of teaching, such as those obtained with the TDOP instrument, can be useful in three ways, Hora says.

TDOP provides insights into teaching practice at departmental and/or institutional levels. Data provided from rigorous classroom observations provide accurate and detailed accounts of teaching that can be used to track changes in instruction over time, evaluate the effectiveness of instructional interventions, and increase administrators’ appreciation for the types of instruction taking place in their departments and institutions.

TDOP can inform faculty professional development sessions. When incorporated into formal professional development efforts, such as new faculty orientations, these accounts can spark self-reflection for individual faculty and help faculty developers gauge an individual’s growth over time.

TDOP provides more accurate accounts of classroom teaching for policy makers. Policy makers often encourage faculty to set aside lecturing in favor of interactive teaching methods. In doing do, however, they oversimplify the problem. With more accurate descriptions of teaching, policy makers can target scarce resources toward programs that align research-based practices with practice.

Hora notes that TDOP could also explore the relationship between classroom teaching and student learning. His study did not aim to determine how different types of instruction influence how students studied and ultimately learned the course material, but he recommends that future research should include this dimension.