Ecology at Play

UW–Madison video game teaches respect for the environment

September 8, 2017 | By Lynn Armitage

Mike Lawton, a Milwaukee teacher, created an ecologically themed board game, “Dwindle,” after playing “Econauts.”

Mike Lawton loves his job as a science teacher at Rufus King High School in Milwaukee. “My greatest reward is when students come up to me and say, ‘Wow, this is the first science class I have ever liked,’” he says.

Perhaps students enjoy his class because so much of it is fun and games—literally. Whenever he can, Lawton uses educational games to teach about complex scientific concepts, like atoms. “My students don’t even realize they are piecing together this scientific model in their head because they are simply trying to win the game.”

Learning through gaming is a teaching strategy Lawton discovered as a science instructor in UW‒Madison’s PEOPLE program—a rigorous, three-week pre-college program in the summer for low-income students, students of color, families, teachers and counselors. During a professional development course at PEOPLE, Lawton was introduced to “Econauts,” a multi-player, interactive video game developed at UW‒Madison that answers a fundamental question: “How do the choices humans make affect our environment?”

In the game, students, as avatars, learn how certain industries, such as logging, farming and mining, affect lakes and their ecosystems. The goal is to make money while competing with other players for resources. While cutting down trees, planting fields or harvesting iron ore, players may or may not impact the environment negatively. If their actions harm the environment, players will see the runoff, pollution or algae bloom after a short time lag.

“Econauts” is a multi-player, interactive video game developed at UW‒Madison that teaches students how their decisions affect the environment.

Lawton says he was hooked after playing the game, and he has been using “Econauts” ever since to teach science. “I have designed my own three-week curriculum in the PEOPLE program using ‘Econauts’ and two other virtual games.” The Milwaukee educator says he has been encouraged by the learning outcomes he has seen through educational gaming. “I definitely see more connections and engagement happening with students.”

The PEOPLE instructor who introduced Lawton to “Econauts” is Robert Bohanan, the outreach program manager for the Wisconsin Institute for Science Education and Community Engagement (WISCIENCE). Bohanan was instrumental in the development of the video game. For the last five years, the ecologist has used “Econauts” to teach about complex ecosystems to scientists, science teachers, and middle and high school students because he says it is difficult to understand cause and effect through traditional teaching methods in the classroom.

“When students play ‘Econauts,’ they make decisions that have direct ecological impacts, and that is really exciting for them to see!” Bohanan is heartened by how this video game could make players better stewards of the environment. “One thing I have seen in almost every group of students who have played the game is that they have at least considered changing their behavior when they kill fish, even though there is no negative consequence to killing fish.”

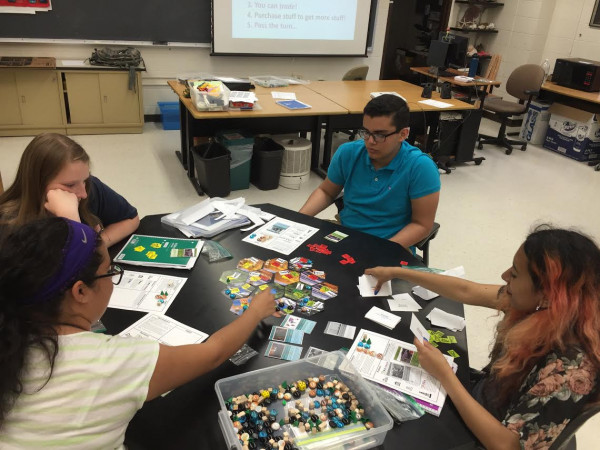

Students in the PEOPLE program play a round of “Dwindle” to learn how to manage limited resources. Photo courtesy of Mike Lawton

“Econauts” is part of the growing video game portfolio of Gear Learning, an education game studio at the Wisconsin Center for Education Research in the School of Education. Gear Learning Director Mike Beall, who was involved in the creation of “Econauts” as a 3-D artist and designer, is impressed by the way that Bohanan has leveraged the game to teach his students about lakes—like how algae forms and how pollution develops.

“Robert saw almost immediately that this game could translate complex information into something more digestible. He will take students out to the lake on field trips and then play the game with them,” and Beall says his team is learning from this highly effective teaching method. “The way that Robert is using the game in conjunction with real-world activities is helping Gear Learning understand how to make our other games better.”

A few years ago, Bohanan challenged Lawton and other teachers in his PEOPLE class to create their own educational games. Bohanan jokes that due to the difficulty of the assignment, “It brought people to tears.”

However, with Lawton, this creative challenge had the opposite effect. “The gears in my brain started turning right away, and I filled a whole notebook with ideas,” he recalls.

Robert Bohanan, an ecologist at WISCIENCE, helped develop “Econauts” and often reinforces learning with field trips to the lake. Photo courtesy of Amber Levenhagen of the Verona Press

The end product was a board game that Lawton dubbed, “Dwindle.” The big takeaway from the game is that nothing lasts forever. “I wanted students to learn that the earth is a system that does not have infinite resources and the key to making them last is to use them as efficiently as possible.” Lawton received a stipend from the National Science Foundation to develop and test “Dwindle,” and he would eventually like to make the game available to the public.

Inspired by some of the content in “Dwindle,” Bohanan continues to work with Beall on improving “Econauts.” He says that in the next iteration of the video game, he wants to include “Dwindle’s” idea of limited resources, and possibly the imposition of fines. “Many students have suggested that there should be a monetary cost for harming the environment. I think that’s a great idea!”

While he does not consider himself a gamer by any means, Bohanan says that educational gaming has changed the way he approaches teaching. “Now, I don’t just automatically think about a static, written curriculum. I think, ‘Is there a way that we can gamify this?’”