Games Based Assessment: Capturing Evidence of Learning in Play

January 20, 2013

Richard Halverson

Why do students like video games? Well-designed games reward players for mastering required content and strategies. They facilitate players’ advancement toward more complex activities, engage players in organized social interaction toward shared goals, and allow players to monitor their progress. Could video games be used to assess student achievement?

UW–Madison education professor Richard Halverson believes that learning scientists and assessment designers can, and should, develop methods for using games to assess student progress. Current assessment methods in classrooms often lack the motivating and information-rich ways that games capture data about learning. Game play can provide a powerful new form of assessment.

Halverson and colleagues Elizabeth Owen, Nathan Wills, and Benjamin Shapiro build video games based on cutting-edge science research, then capture game-play data as evidence of player learning.

Their game-based assessment (GBA) project at the UW-Madison’s Games+Learning+Society (GLS) Research Center is funded by the National Science Foundation and directed by Halverson and Kurt Squire.

Game-Based Assessment Model

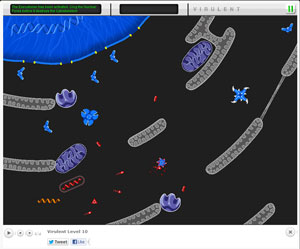

GLS games are designed to promote learning by involving players in worlds that explore regenerative biology, virology, medical technology and limnology. In the game Progenitor X, for example, players cultivate stem cells to replace diseased tissues and organs. They guide viruses into cells in the game Virulent and how explore how implicit bias influences perceptions in professional settings in the game Fair Play.

The flow of the game encourages players to navigate the norms, roles, and the narrative structure of a simulated world. The GLS design team brings together content experts, game developers and programmers, artists, educators, and learning scientists in a collaborative process to create games around specific learning goals. The team identifies subject matter that can be best expressed in a particular video game to enhance the players’ understanding of a particular education topic.

A GLS game consists of several chunks of content arranged according to current practice in a given domain. The content model for the game Progenitor X focuses on the processes scientists use to manipulate stem cells in the lab and use them in treatment. Such basic science questions are often overlooked in public discussion. It’s possible that game-based experience with the science of stem cells could encourage young players to consider this kind of research as a career option, and may enhance the public understanding of the science.

A design team first determines the relation between the subject matter content and the flow of the game to understand whether players can access chunks of content through game play. Game designers test beta versions of games with student players. They collect data from students’ mouse clicks and look for patterns, as in education data mining. Game designers then develop records of in-game player interaction that are then used as evidence of learning.

GLS includes cycles of formative assessment, which provide ongoing feedback to game players. Games customize difficulty levels to match and challenge each student’s ability. A good game balances this ongoing assessment with a compelling story line and engaging adventures.

Good games also inspire communities of practice. These amplify in-game learning by fostering collective intelligence and participatory cultures.

To bring out the full potential of games for learning means that “little g” games, such as Progenitor X, should be nested in “big G” game contexts that activate play-based learning in social- and knowledge-rich interactions.

Halverson says the guiding question of the GBA design was to determine whether we could say anything interesting about learning with structured in-game data. Good games translate the educational content to the player through compelling challenges and strategies, while poor games allow players to bypass the content by simply pressing buttons and “gaming” the environment. The GLS Game-Based Assessment group’s early research can document the differences between players who are fooling around with the game vs. players who are trying to learn the science practices embedded in the game design.

These kinds of distinctions will help games researchers to show how games can serve as assessments that generate reliable evidence for content learning to formal education environments. The GLS group is partnering with the Learning Games Network and developers across the country to build game-based assessment tools into a new generation of learning games.

When that happens, Halverson says, we’ll liberate the potential of games—as the ultimate disruptive technology!—to shake and rattle the social conventions that limit the potential of learning technologies in schools.

More about Progenitor X: http://www.eriainteractive.com/project_ProgenitorX.php

More about Virulent: http://www.eriainteractive.com/project_Virulent.php

More about Fair Play: http://www.eriainteractive.com/project_Pathfinder.php