Speaking Up for Special Students

May 22, 2018 | By Lynn Armitage

Cha Kai Yang, left, and Miguel Hernandez Bolanos are important members of the ALTELLA team, assisting staff with office tasks.

Cha Kai Yang and Miguel Hernandez Bolanos are thrilled to be working at the University of Wisconsin‒Madison. It is a dream job for 22-year-old Bolanos, a lifelong Badger fan. Yang, 19, says the best part is earning a paycheck.

Yang and Bolanos participate in a community-based program through West High School that finds gainful employment for people with disabilities. They work together at WIDA, a project at the Wisconsin Center for Education Research. Fortunately for these young men, they have been identified and supported as English language learners (ELLs) with significant cognitive disabilities—a K-12 population in the U.S. largely overlooked by the academic assessment community.

Yang’s native language is Hmong; Bolanos, who lives in a Spanish-speaking home and understands some English, mostly uses sign language to communicate.

“Most ELLs like Cha Kai and Miguel end up in special education, where many teachers don’t have backgrounds in English language development. Likewise, English language teachers generally don’t have special ed training,” says Laurene Christensen, a principal investigator at WCER. Once students with cognitive impairments get placed into special education classes due to the language barrier, Christensen says they typically never exit these services, so any chance of English language development falls by the wayside.

Federal law requires each state to assess the language proficiency of ELLs with significant cognitive impairments. However, many states have never performed these assessments due to a lack of research on this special population of students.

Enter ALTELLA, the Alternate English Language Learning Assessment project launched by WCER this year to ensure that these underserved learners receive the English language instruction they are entitled to by law.

ALTELLA is a partnership between WCER and state education departments in five states—Arizona, Michigan, Minnesota, South Carolina and West Virginia— and funded by a $1.3 million grant from the U.S. Department of Education to the Arizona Department of Education. ALTELLA’s mission is to research how educators instruct and accommodate ELLs with significant cognitive disabilities to help states develop their own English language assessment tools for this overlooked subgroup of students.

“We are all trying to work together to learn more about this small group of cognitively challenged English learners who have fallen through the cracks because they need to be learning English in school, too,” says Christensen, who also serves as ALTELLA’s project director.

To that end, ALTELLA staff has conducted nearly 80 classroom observations and teacher interviews in seven states. Their goal is to observe 100 classrooms before the project ends Sept. 30.

Although still collecting data, one ALTELLA researcher was eager to share some preliminary findings. “We’ve discovered that in the mainstream school setting, these students are rarely supported in learning English, yet get instruction in English,” says Melissa Gholson, an assessment expert for special student populations. Teachers may think these students are unable to process information due to a very severe cognitive impairment, when they simply can’t understand the teacher’s language.

Gholson says trying to determine who these students are is one of the biggest challenges. “Of the seven states we have observed, we have found no formal policies on how these students are identified.” Without a proper definition, the learning needs of these special students cannot be met appropriately, ALTELLA researchers write in a recent brief.

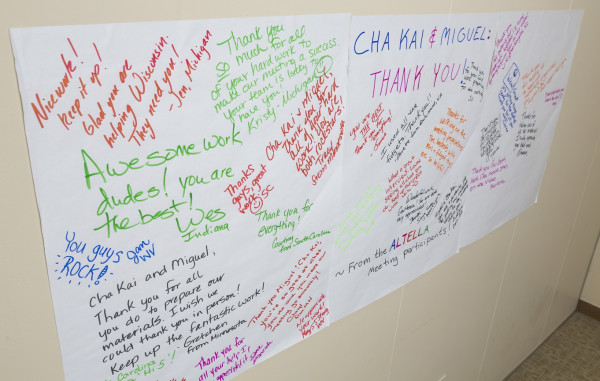

Colleagues show their appreciation to Cha Kai and Miguel for all they do to support WIDA and ALTELLA staff.

Teacher Aimee Seiler understands this identification problem all too well. All of her second- through fifth-grade students at the Newcomers Center in Kentwood, Mich., have been in the U.S. for less than a year, and none of them speak English. Instead, the sounds of Swahili, Nepali, Hakha Chin and other foreign languages fill her classroom daily. Seiler believes she has two to three students with significant cognitive disabilities, but there is no way to know. “One student, in particular, has failure to progress. While I suspect he might be cognitively impaired, no one is available in our district who can interpret Swahili for an IQ test, so I can’t really assess him.” She is hopeful that the ALTELLA project will help inform a proper assessment before this student transitions into a general education setting next year and, as Christensen suggested earlier, “falls through the cracks.”

Yang and Bolanos are important members of the ALTELLA team. For 10 hours a week, these valued employees assist the WIDA and ALTELLA staff with various office tasks (as seen in this video), such as scanning and shredding documents, delivering mail, watering plants, preparing presentation folders and sending out thank-you cards to teachers.

“I really enjoy working with them,” says Fatima Rivera, a WIDA client services specialist. “They are fast workers and are becoming very independent. We give them work, and then they give back to us tenfold with their great work ethic and attitude.”

The end goal is always to get students jobs, says Blake Hamann, a special education assistant with the Madison Metropolitan School District and job coach helping Yang and Bolanos transition into adult community living. “Sometimes our students start out as volunteers to get used to employer expectations. But we believe they should receive full pay and full employment, like anyone else.”

Yang chimes in with a resounding, “Yes!” He says his dream job is to work in the foodservice industry someday.

Researcher Gholson, who worked with disadvantaged students in West Virginia for 25 years, enjoys hearing about the progress of Yang and Bolanos. “It’s the most exciting part of the ALTELLA project,” she says, “to see how students with significant cognitive impairments can be successful in the world of work and live a high-quality life.”