WCER Experts Explain Critical Intersection between Education, Health

Capitol Briefing Highlights How More Schooling Leads to Better, Longer Lives

October 8, 2019 | By Karen Rivedal, WCER Communications

At a Capitol briefing on Oct. 3, four WCER researchers and other experts described links between education and health.

MADISON ─ University researchers and evaluators working with rural schools, the community-school model and Native American communities in Wisconsin shared their expertise and latest evidence-based findings recently in a public hearing at the state Capitol focused on the critical intersection between education and health.

“Better educated individuals live longer, healthier lives than those with less education, and their children are more likely to thrive,” says Karen Odegaard of the UW Population Health Institute, which helped organize the event. “This is true even when factors like income are taken into account.”

About 100 people filled a hearing room for the Oct. 3 panel presentation, sponsored by the institute’s Evidence-Based Health Policy Project, in collaboration with the Wisconsin Center for Education Research, part of UW−Madison’s School of Education.

WCER researchers Craig Albers, Annalee Good, Marlo Reeves and Nicole Bowman presented, among other panel members including two administrators from the Madison Metropolitan School District, a community-engagement leader from the rural Algoma School District, and a Native American social behavioral researcher from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas School of Public Health.

In introductory remarks, Odegaard noted national research shows more schooling is linked to better job opportunities, increased social supports and higher income, with each additional year of schooling yielding 11 percent more income annually. Education also helps people live measurably longer lives.

“On average, college graduates live nine more years than high school dropouts,” Odegaard says. “Higher levels of education can lead to a greater sense of control over one’s life, which is then linked to better health, healthier lifestyle decisions and fewer chronic illnesses.”

Rural schools face unique wellbeing challenges

But the reverse also is true, as children and youth with unaddressed mental and behavioral health issues often encounter more challenges in school that in turn lead to short- and long-term life consequences.

Craig Albers

At WCER’s Rural Education Research and Implementation Center (RERIC), Craig Albers and his team are studying the self-identified needs of Wisconsin’s rural schools, including the problem of how best to address their students’ mental and behavioral health issues. Feedback from schools demanded it.

“As we've traveled throughout the state … the most common and most frequently mentioned issue is mental and behavioral health,” says Albers. “If a child is not strong emotionally, if they do not have mental health wellness, then this has trickle down effects to academics, to disciplinary referrals, to disciplinary issues. It increases the likelihood of disengagement, school drop-out.”

It’s a growing problem for all schools, but districts in more isolated parts of the state show more unmet mental health need, RERIC’s research shows. Reasons can include lack of access, fewer school and community resources, and more difficulty hiring, training and retaining mental health professionals.

"Mental and behavioral health and wellbeing is something that cuts across geographical contexts, economic levels, racial and cultural categories, and pretty much any other demographic category that we can think of. This is not (just) a rural issue," Albers says. "However, what we want to bring attention to within RERIC is that there are unique considerations and some unique barriers to addressing these issues within rural schools and communities."

WCER researchers focused on rural schools are using partnerships to address mental and behavioral wellbeing among students.

Surveys done as part of RERIC’s research show 87-90 percent of Wisconsin principals in rural areas reported there were students in their schools in the past 12 months who needed mental health services but did not receive them, compared to only 83 percent of principals in the state’s large suburbs and 73 percent of principals in its cities answering the same way. (The surveys break down Wisconsin’s rural districts to one of three categories along an increasingly removed gradient: fringe, distant and remote.)

Wisconsin principals in rural areas also reported larger percentages of students with mental health needs, with 22-41 percent of them identifying 21 to 50 percent of their students having such needs. Only 12 percent and 13 percent of principals in large cities and suburbs, respectively, said the same.

“We’re not just talking about students with a diagnosed mental health disorder,” Albers notes. “We are talking about general well-being, which includes mental and behavioral well-being.”

In school, Albers reported, unmet need for mental health services can lead to chronic absences, disruptive behavior, lower achievement, more disengagement and a greater likelihood of dropping out.

These challenges grow as youth age into adults, as national studies show students with unmet mental health needs are more likely to develop significant mental health problems in adulthood, to be involved in the criminal justice system and to have interpersonal and relationship problems.

The best chance to prevent or reverse those negative outcomes lies in early intervention, Albers notes.

“It’s much more difficult to address, more challenging to minimize these impacts later,” he says. “Within a school setting, when children are young, we can address some of these issues that are starting to emerge and we can be effective. We can set these youth up for success, not only in school but in life.”

Albers says evidence-based strategies for schools that hold promise include:

- tiered intervention response models.

- professional development of school staff to better identify students in need.

- telehealth/teletherapy tools.

- community providers offering services within schools.

- right-sizing of programs developed for use in bigger cities and suburbs.

“We’ve come to appreciate that there’s not one approach that’s going to work,” Albers says. “It really needs to be a variety and range of approaches in different settings provided by different people.”

In the rural Algoma School District outside Green Bay, for example, school and community members built a wellness center attached to the high school in which retirees can work out next to students.

“Communities do hold the solutions and have the power to make sustainable, equitable changes for health and opportunity for all,” says Teal VanLanen of the Algoma District. “We start small and we build from there. We bring together assets of the community and we cultivate a shared vision or aim.”

Community schools address health

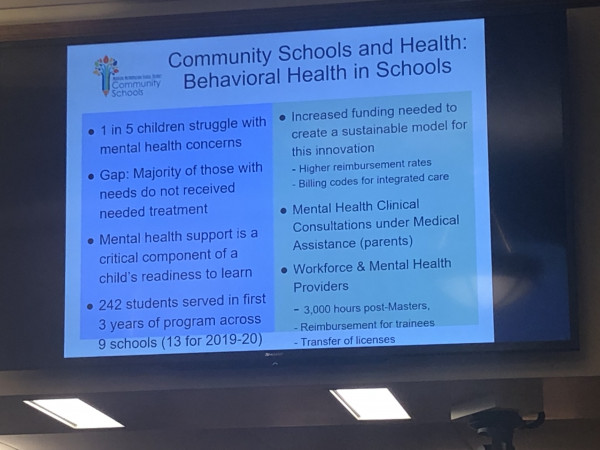

As part of the hearing’s second presentation, WCER researcher and evaluator Annalee Good and doctoral candidate Marlo Reeves discussed how the community school model works to coordinate health and educational opportunities for students and their families, among other benefits.

The community-school model provides social services to students and their families that are customized to the needs of the school and surrounding area.

Both have examined community schools’ implementation and outcomes locally and around the state: Reeves specializes in the educational evaluation of K-12 spaces, while Good is co-director of WCER’s Wisconsin Evaluation Collaborative (WEC), which conducts evaluations of programs, curricula and initiatives serving students in the state’s preK-12 educational system and in the community.

“The most evident of the results that we've seen (in community schools) are changes in school climate, neighborhood climate, and the sense of belonging within the community,” said Reeves. “Disciplinary actions within schools have changed -- lower suspension rates, lower referrals, across the different districts that we've been able to work alongside."

Community schools by design offer an expanded array of social services and other programs based around the model’s four main pillars: integrated student supports, expanded and enriched learning time, active family and community engagement, and collaborative leadership and practices.

Annalee Good

Services at community schools also are customized for the school and surrounding community.

“One of the things that’s most promising about the community schools model is that it’s a community’s response to a community’s identification of their own needs,” Good says. “And often what comes out of that is communities being really innovative.”

Health services and family counseling was one need identified in Madison’s community schools, according to Aronn Peterson, the district’s community schools manager.

“Health has a clear correlation to academics, attendance and behavior,” Peterson says, noting a mobile community flu clinic is one health program being offered through a partnership with MMSD, Hy-Vee, United Way and Dane County Public Health in all four of the district’s community schools: Leopold, Mendota, Hawthorne and Lake View elementaries. “(The idea) came from parents who lacked access to getting their kids vaccinated. (Getting the flu) does lead to missed school time and absenteeism for students.”

Other examples of health-related programs in the district included a six-week running and walking club at Lake View that nearly all students took part in, Peterson says, and UW Health-sponsored wellness days for staff and students focused on health awareness and healthy behaviors.

Members of the panel included, pictured from left, Karen Odegaard, Teal VanLanen, Craig Albers, Marlo Reeves, Annalee Good, Aronn Peterson and Armando Hernandez.

In addition, Armando Hernandez, assistant director of integrated health for the Madison district, highlighted some of the mental health and trauma care programs being offered through partnerships with organizations including Catholic Charities and Journey Mental Health Center.

One program, known as Bounce Back, begins with a universal screening of third graders to target those struggling with a traumatic event and offer them a 10-week, evidence-based intervention program. Last school year, more than 1,000 third-graders in the district were screened and the district subsequently delivered the program through a partnership between school staff and licensed mental health clinicians in 20 schools to groups ranging between three and six students each, Hernandez said.

‘Different thinking’ to tackle tribal health disparities

Finally, WCER researcher and evaluator Nicole Bowman, (Mohican/Munsee), and Carolee Dodge Francis, an associate professor at the University of Nevada and a member of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin, presented on their experience with culturally responsive approaches to evaluation research with tribal nations, including highlights from case studies featuring the intersection of education and health.

The pair began by sharing research on severe health disparities among Wisconsin Native Americans, including four times the diagnosis and mortality rate for Type-2 diabetes and an average age at death of 63 for Native Americans, compared to 77 years for whites. Infant mortality rates for Native American children also are 69 percent higher than those of white children, the data shows, while Native American children have the highest age-adjusted suicide rate (at 2.5 deaths per 100,000) across all races.

Nicole Bowman, left, and Carolee Dodge Francis discussed health disparities afflicting Wisconsin Native Americans.

Noting most Native American children attend majority-white schools, Francis says, “They’re not reflected in the student body, they’re not reflected in the faculty. So they feel like they don’t belong.”

What’s more, fewer American Indians in Wisconsin complete high school – 86 percent compared to 91 percent for all races – and only 13.8 percent had a bachelor’s degree or more, compared to 28.43 percent for all races, according to 2016 data from the Great Lakes Inter-Tribal Epidemiology Center.

“We have to do our work differently in order to have different outcomes,” Bowman says.

Keys to working differently with the state’s 12 tribal nations include the need for researchers to expand their on-the-ground experiential knowledge and deepen social networks to build trust among members.

“Doing your focus groups is very different than just hanging and having a meal (with subjects),” Bowman counsels researchers. “It might seem like a real simple step, but just get out there, get some fresh air, get out of your office. We have to get out and we have to experience life with the folks that we are serving. It’s super-important.”

Many factors drive health outcomes

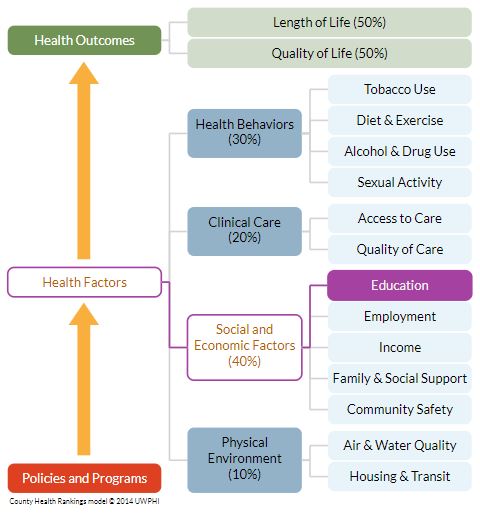

Overall, the health and education briefing was the third in a series being presented by the EBHPP on the social and environmental factors that help drive health outcomes, collectively known as the social determinants of health. The first two presentations, held at the Capitol in November 2017 and March 2018, covered the health-related impacts of family and social supports, and housing, respectively.

County Health Rankings model shows a variety of factors that combine to affect health outcomes, for good or bad.

EBHPP Managing Director Sam Austin said the goal is to provide research presentations on all eight of the social and environmental factors comprising the County Health Rankings model of population health ─ a comprehensive definition of key elements that drive health outcomes developed by the Population Health Institute. The remaining social and environmental factors in the county model of population health are employment, income, air and water quality, community safety and transit.

“Where we live, learn, work and play affects our well-being,” Austin says.

Beyond social determinants, the model includes health-related behaviors, such as smoking and drinking, and clinical care – both the quality of it and people’s access to it. The key is how all the factors interconnect to determine individual and community health outcomes, presenters said.

“We know that we can all make sure that we’re eating healthy and moving our bodies and getting to our annual checkups,” Odegaard says. “But… there’s much more than that to health. The quality of our homes, the safety of our neighborhoods, and our chance for a good education all have a major role to play in how long and how well we live.”

All speaker slides and background/resource materials from the health and education briefing are here.

The EBHPP works to connect research and expertise from university, government and community sources for consideration in the state’s crafting of health policy. The project is a partnership between the health institute, the La Follette School of Public Affairs and the non-partisan Wisconsin Legislative Council, which provides legal advice, guidance and research services to state lawmakers.

The EBHPP receives grant funding from the UW School of Medicine and Public Health’s Wisconsin Partnership Program and the UW−Madison Chancellor’s Office, plus contributions from project partners. It was formed in 2002 with financial backing from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s State Health Policy Forums initiative.