WEC Evaluators Recommend Sharing Best Practices as Student Career Planning Spans State

Completion of final projects seen as "powerful practice" in state-required program

January 14, 2020 | By Karen Rivedal, WCER Communications

A student poster from Northland Pines Middle School demonstrates a capstone project in the ACP program.

A new study by evaluation professionals at the Wisconsin Center for Education Research (WCER) finds that sharing specifics about five identified best practices will be important as a state-required academic and career planning (ACP) program takes hold in schools and districts across the state.

“Now that implementation has been happening for several years and is quite widespread, we can begin to focus more on best practices and novel, successful approaches that others can learn from,” says Robin Worth, who leads the ACP evaluation team from the Wisconsin Evaluation Collaborative (WEC) at WCER, housed within the School of Education at UW−Madison.

ACP plans, required under state law since 2017, are intended to get students in grades 6-12 thinking sooner about what they’re good at and what they might want to do after high school – whether that means a university, technical college, the military or the world of work immediately.

The development of “school-wide cultures” of ACP, with responsibilities for the program shared across many types of staff, also is growing, the evaluation finds, though gaps in student participation by race and region remain. But including a final project in ACP plans – one of five best practices – may help boost student involvement because it tends to make the program feel more relevant, the report says.

“Final projects often compel students to take ACP more seriously and be more invested in it,” Worth says. “This is important because a whole host of benefits can be derived from a quality ACP program, but only if students buy into its relevance and importance, and then participate in an engaged way.”

Promulgated by the state’s Department of Public Instruction (DPI), the program has taken shape in middle schools and high schools statewide as an umbrella of college- and career-related activities that can include five practices identified to evaluators as “powerful” by students, educators and families: job shadowing, mock interviews, resume-building, one-on-one conferencing/advising and the final projects, usually in the form of either a portfolio presentation that spotlights a student’s high school accomplishments and experiences or an exit interview or both.

And of the five, students most often cited final projects as their school’s most beneficial ACP-related activity, along with job-shadowing, according to the evaluation.

“You’re told your freshman year, you need to keep all this important stuff (in a portfolio),” a student at Barron High School in northwestern Wisconsin told evaluators. “When you get to your senior year, finally being like, ‘Wow, my freshman year I was this, and my senior year I’m this,’ the realization that you have come so far, also really makes the portfolio worth it in the end.”

A Baraboo High School teacher also praised the final project’s presentation as a helpful showcase of accomplishments for students, especially those who may not have perfect grades.

“For example, the student who works from 10-12 every night and then comes back to school, (or) another student who talked about her ability to do school without the internet at home,” the Baraboo teacher says. “There’s the possibility to get recognition for having grit and perseverance, beyond grades, and a work ethic and feedback on how essential that is.”

Evaluation based on case studies, surveys, data

WEC has been doing a longitudinal, mixed-methods evaluation of the ACP program since spring 2015, starting with a needs assessment and followed by three consecutive annual reports covering DPI’s rollout and implementation of the program, from a 25-district pilot project in 2015-2016 to a statewide requirement starting in fall 2017. The latest evaluation – and fourth annual report -- covers academic year 2018-2019, with up to an additional four years of ACP evaluation work expected in annual contracts.

WEC qualitative researcher Robin Worth was Principal Investigator on the 2018-19 ACP evaluation for the state Department of Public Instruction.

The evaluations are based on case studies, a statewide school-level survey, student outcome data such as graduation rates and GPA, as well as state- and local-level measures of the ACP-related activities offered and participated in, such as work-based learning, dual-credit courses and Advanced Placement courses.

Worth says site visits are a uniquely valuable type of work method for evaluators.

“I’m always amazed at the things we find when we go out into the field,” Worth says, noting the practical value of first-hand observations. “It’s so important to our work to ‘get our hands dirty in the weeds.’”

The latest evaluation also focuses on describing the various ways final projects are structured and operated, with all 10 case-study districts reporting multiple benefits from implementing them:

- Recognition – Allowing students to showcase their work/school experiences and plans.

- Experience – Providing the opportunity for students to gain interview and presentation skills.

- Accountability – A means to compel students to take ACP and future planning more seriously.

- Relationship-building – Providing students a chance to capitalize on relationships between students, schools, teachers, families, community members and employers.

In addition to the evaluation, Worth’s team has developed a nine-page brief for Wisconsin educators with more details about implementing final projects in high schools and middle schools.

Biggest reveals, most surprising findings

Worth said the evaluation’s biggest revelation about final projects appears to be how crucial they can be to the success of the ACP program overall. Knowing they are working toward a tangible end product that must be finished in their senior year can make students more eager to continue taking part in the various program activities in a meaningful way throughout their middle and high school years.

One of the evaluation’s most surprising findings concerning final projects, Worth says, involves the students’ preferred audience for a portfolio presentation/exit interview. Students report that these capstone experiences were “much more valuable” if they were done for external audiences – such as employers and community members – rather than just for their regular teachers and/or peers, the report found.

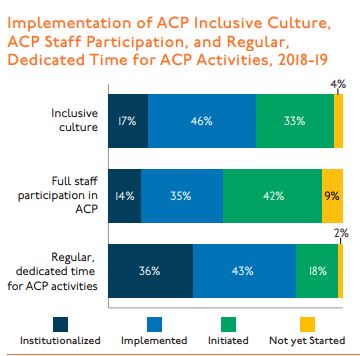

Evaluators are seeing ACP-related staff participation and program activities grow and become more institutionalized in many Wisconsin school districts.

Presenting final projects to external audiences was deemed better in part because students felt that approach was more authentic, and because it allowed them to get feedback from adults who didn’t know them, or who at least knew them differently than their teachers did, the evaluation found.

“This provided a new perspective, often reported as being uncolored by the familiarity, expectations, images, histories, etc., that teachers had of them,” Worth says. “Essentially, they tended to report that they found the external feedback more objective.”

Pitching to outside professionals also could have some practical benefits for graduating seniors.

“They are talking with employers that want to employ them,” an Antigo High School teacher says. “That is huge. They could walk out and get a call asking if they want to do an apprenticeship.”

In addition to studying several high school ACP programs, the evaluation also looked at one middle-school version. Worth says she was most impressed with “how articulate and knowledgeable” middle school students were when they talked about career exploration and interests in final projects.

“I was not previously sold on how important or developmentally appropriate this work is at the middle school level -- although the research tends to show that it is -- until I saw it first hand,” Worth says. “I’m now a believer that when done well, this kind of work is very beneficial to younger students as well as high schoolers, and does not equate to ‘tracking’ or some of the other ills that critics attribute to it.”

Recommendations for DPI in the evaluation include:

- continue promoting the five best practices and share resources about them.

- consider developing and providing professional learning opportunities for school staff to support ACP.

- continue investigating dedicated time for ACP.

- pursue additional investigation into student accountability measures related to ACP.

- pursue research on equitable implementation of ACP in terms of access and participation gaps.

Evaluators say they found “relatively few” challenges or drawbacks associated with final projects, but they advise educators to avoid excessive “paperwork or busywork” in portfolio creation and to provide enough time for students to prepare their portfolios and presentations. Worth’s team members for the fourth annual ACP evaluation are Grant Sim (co-PI), Jessica Arrigoni, Brie Chapa, Journey Henderson and Daniel Marlin.

--------------------

ABOUT WEC: WEC evaluators support youth-serving organizations and initiatives through culturally responsive and rigorous program evaluation within the preK-12 education system, including school districts, professional associations, state agencies and education-based community organizations.